The Murky World of ZFC Zero Friction Cycling: Botched Testing, Frigged Results

This article is not questioning the merits of chain waxing vs other methods. It’s an engineering investigation into the methods, results and the marketing behind Zero Friction Cycling who appear to be not as legitimate or technically adept as they may portray.

Zero Friction Cycling is an operation run by Adam Kerin, a former policeman with no formal engineering qualifications or engineering experience (His words). Adam’s business revolves around selling friction-reducing products through his YouTube channel, Facebook, Instagram, and his accompanying website.

It’s a HOBBY??? Or is it

Adam is keen to stress that ZFC is a “Hobby”. Despite this, he employs one person to sell his retail goods and proudly displays his business awards from the “Quality Business Awards” website on his website.

His email signature would also leave you puzzled for someone who claims to be testing chain lubricant as a “hobby”, it comes complete with opening hours! It looks like a commercial operation. Furthermore, the claim that ZFC is “independent” despite selling various lubricants is dubious.

A quick buck without putting the work in

A few years ago, Adam reached out, requesting access to test data, protocols, and detailed information related to tribological practices – data that is typically sensitive and not freely shared. Not surprisingly, he received a similar response from Muc-off and other companies, though he chose not to publicize those rejections as much. Adam appears somewhat naïve about what information is customarily disclosed in the business world, particularly given that, in this case, we are essentially competitors.

His narrative seems to suggest that anyone who is not entirely transparent with their protocols or testing must be concealing something and engaging in questionable marketing practices. The reality, however, is that Adam was unwilling or unable to acquire the required technical standards and seemed reluctant to undertake the necessary research himself.

Nonetheless, Following his request, I responded politely, suggesting that he start with some foundational reading, specifically the book Tribology: Friction and Wear of Engineering Materials by Hutchings. His questions were typical of someone without technical experience or understanding of the field. In response, he claimed he didn’t have the time to read the recommended material:

“Ah yes I won’t quite have time for that unfortunately, my theory is those who know more than me will be able to explain to a non engineer layman, in layman terms why.”

The exchange continued, with Adam insisting:

I should be able to have the correct clear picture without reading engineering books to know what I should sell. If something is fact, there should not be counter information or intuitive question marks…

Adam’s motives became blatantly clear from that statement: he intended to conduct minimal research and focus solely on selling products that he could market at high margins. His claims of independent testing were nothing more than wishful thinking. Adam’s persistent questioning continued, and he eventually asserted – after supposedly consulting with SKF and an unnamed “top bearing supplier” in Australia – that the data I provided was incorrect. His primary assertion was:

“When subjected to vibration, hybrid bearings are significantly less susceptible to false brinelling (formation of shallow depressions in the raceways) between the silicon nitride and steel surfaces.”

Despite my repeated efforts to clarify – seven times in our email chain, to be precise – he either did not grasp or chose to ignore the critical differences between false brinelling and brinelling. False brinelling occurs due to vibrating static load and is associated with static bearings and not those that are rotating.

False brinelling occurs through vibrating static load and is generally not associated with rotating shafts. This photograph from SKF shows the damage clearly as regular dimples, this would not occur in a bearing that was rotating.

This level of misunderstanding was evident throughout our correspondence, illustrating a significant knowledge gap that should be concerning for someone marketing themselves as an expert in tribology for cycling components.

The Ceramic Bearing Narrative

Adam Kerin later published a 27-page article attempting to justify his support for ceramic bearings, but it was riddled with amateurish inaccuracies and misconceptions. He continued to harp on the supposed “fishy marketing” due to the lack of openly available information, failing to grasp the costs (standards are expensive), complexities and proprietary nature of the data he was seeking.

In 2004, Schaeffler, through their bearing brands, developed a martensitic hardened steel that would later carry the trade name Cronitect. This material was exclusively used by Campagnolo for two years from ~2008 in their Super Record bottom brackets. Schaeffler conducted extensive testing of several million cycles to validate the product’s performance in comparison to their regular offering; they were a supplier to Hope at this time. This segment of Schaeffler’s business would eventually evolve into Schaeffler Velosolutions.

Despite well-documented marketing material produced by Schaeffler, Kerin has repeatedly claimed these tests never took place (likely, he could not find it on google) even though it’s widely known that this type of bearing has specific applications—namely, inner ring interference only – due to its poor shock performance. Campagnolo has generally only used the bearing in inner race interference applications.

This dialogue made it abundantly clear that Kerin had little knowledge of S-N curves, the basic loading calculations of bearings or test standards such as Fafnir testing. He also has the deluded mindset that a competitor (Hambini Engineering) would provide this data and knowledge for free.

Even basic calculations are wrong..

Kerin’s continued shallow depth of engineering extend further, as he incorrectly states:

“Torque (turning force) x RPM = power.”

This statement is fundamentally incorrect. Power is calculated as the product of torque and angular speed (in radians per second) for SI, not simply RPM. Even the most junior engineering students would recognize this basic principle. Kerin also claims that power and loss can be measured directly, disregarding the fact that power is not a fundamental unit within MLT (mass-length-time) or FLT (force-length-time) systems, it must always be calculated and is typically timed. Similarly, friction does not have standalone units, it is a coefficient and is always derived through calculations despite his assertions that it can be measured directly.

These misstatements highlight a significant lack of technical understanding, raising concerns about his authority on such topics.

Ceramic Bearings and Vibration – Kerin Ignores his own supplier’s Data

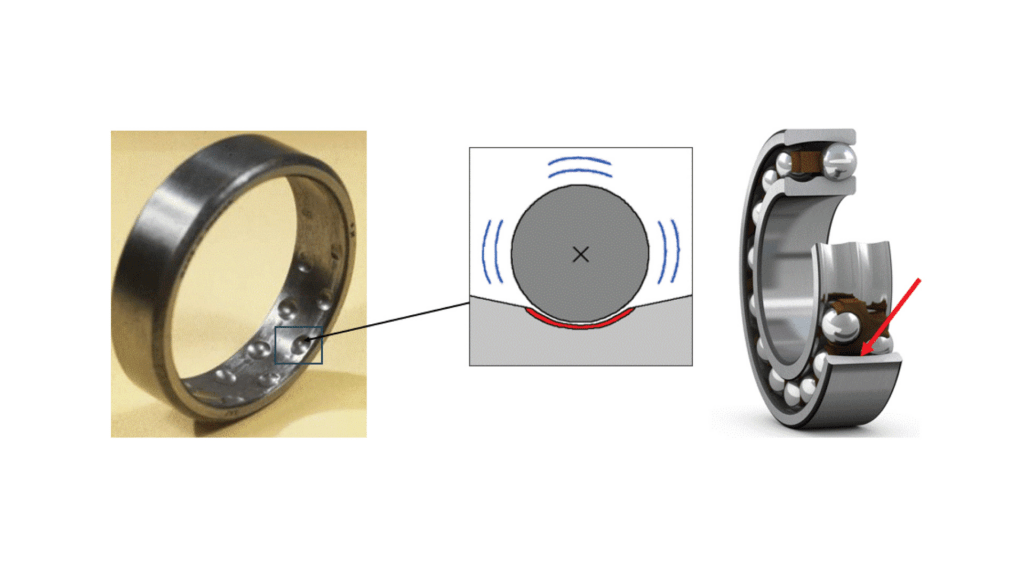

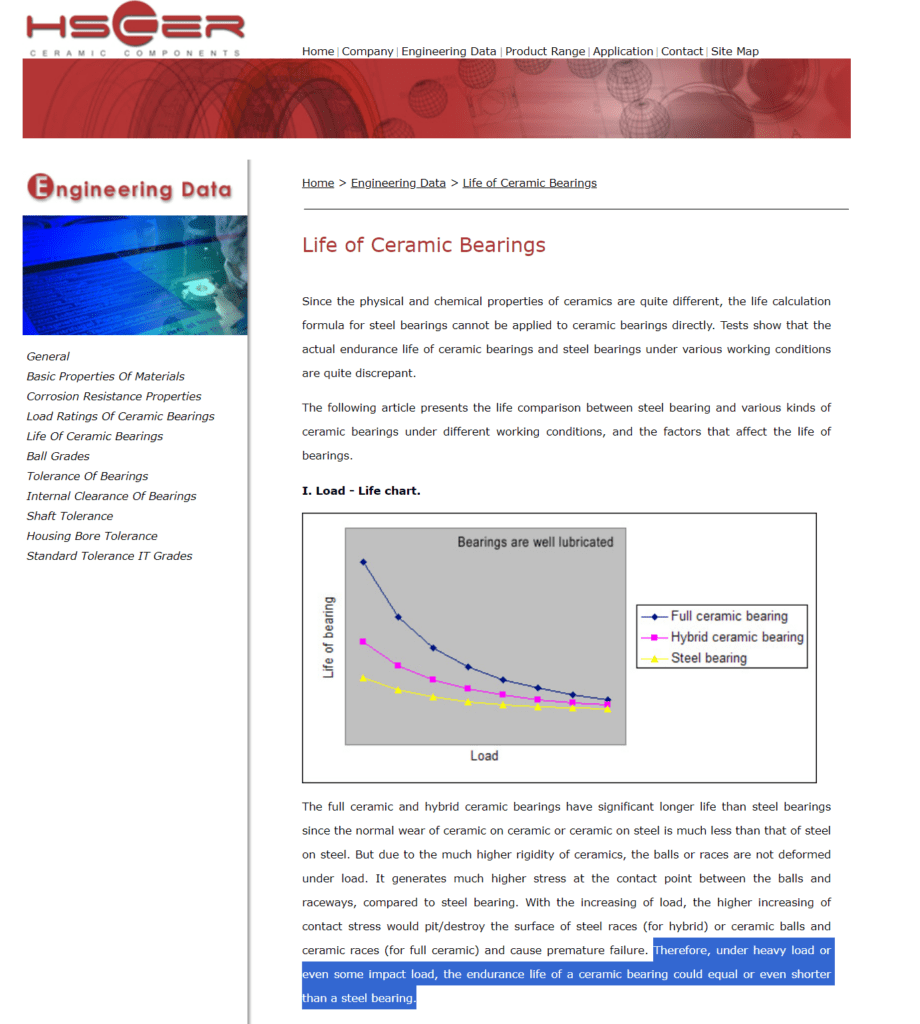

Ceramic bearings are notoriously poor performers under shock and heavy loading, which is why they are not suitable for applications like car wheel bearings and power tools. Instead, they are typically used in high-speed, pressure-lubricated machinery, medical devices or electric motors, where their insulating properties offer distinct advantages.

Interestingly, these conclusions align with data from Kerin’s own supplier, HSC Ceramics, which he conveniently chose to omit and completely contradict in his narrative. HSC states under shock conditions or high loads, ceramic bearing life will be at the very best, equal and more likely to be less than a steel bearing. This is due to a high hertzian contact stress – essentially brinelling.

Kerin’s comments on the matter

Quality hardened steel races are not troubled by harder ceramic balls in cycling application due to vibration.

Had Kerin taken the time to read the recommended material, he would know the difference between brinelling and false brinelling. He would have also understood why plastic cages are a poor choice for highly loaded bearings.

Chain Lubricant Testing: A Critical Examination

At the time of writing, standards bodies such as ISO, DIN, ASTM, and API define basic standards for lubricants; however, there is no specific international standard for testing bike chain lubricants. The main focus of Adam Kerin’s testing methodology is the correlation between friction levels and wear, which is gauged by chain stretch. For bike chains, however, this strategy is essentially unproven.

Currently, there are no peer-reviewed studies or published articles that support Kerin’s chain testing approach, particularly when it comes to cycling. Even though he claims that his methodology is “open and therefore valid,” no acknowledged standards or impartial assessments have been able to verify it. The veracity and precision of the findings generated by his testing techniques are seriously questioned in light of the absence of scientific support.

Flaws in the Testing Setup

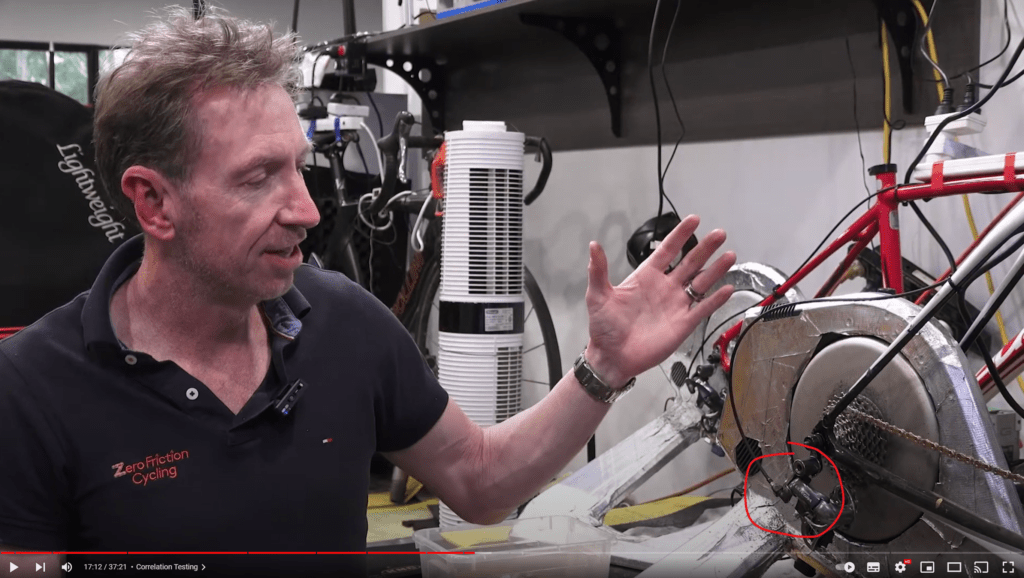

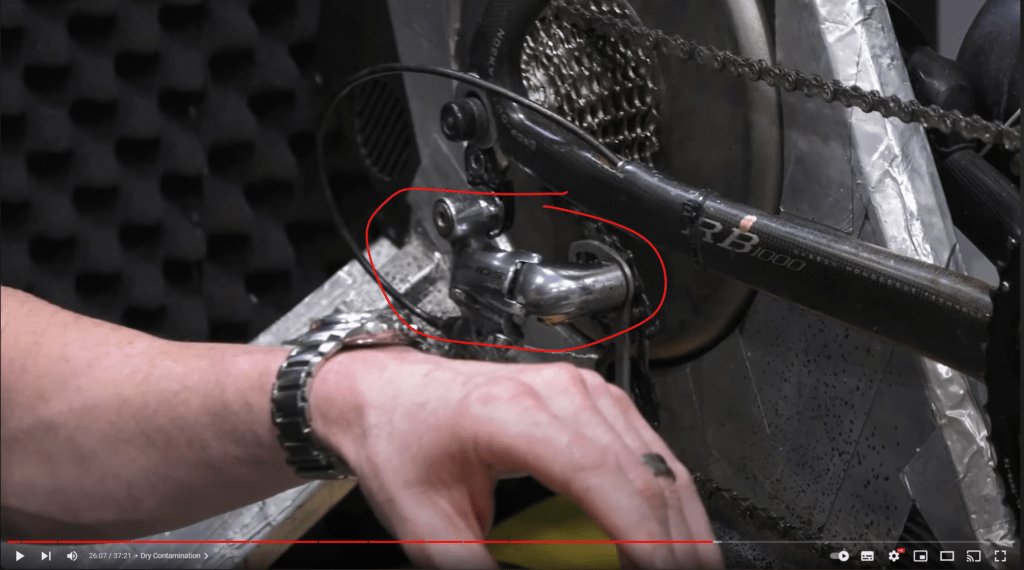

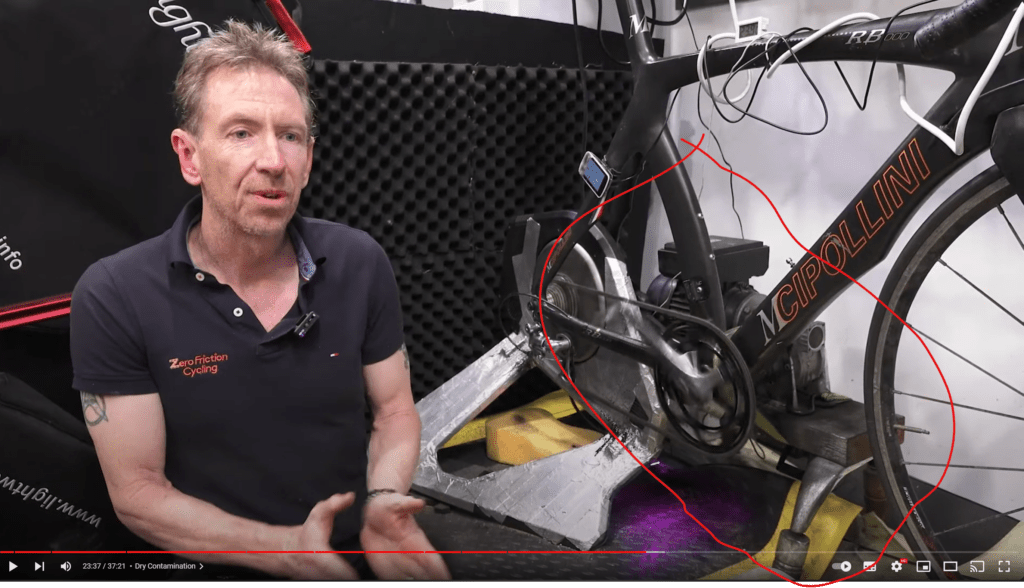

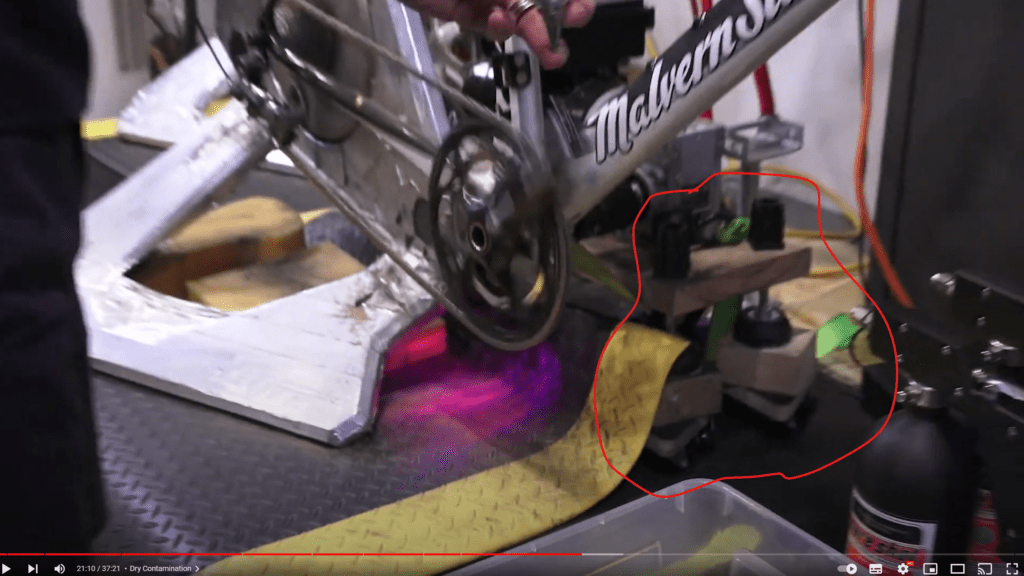

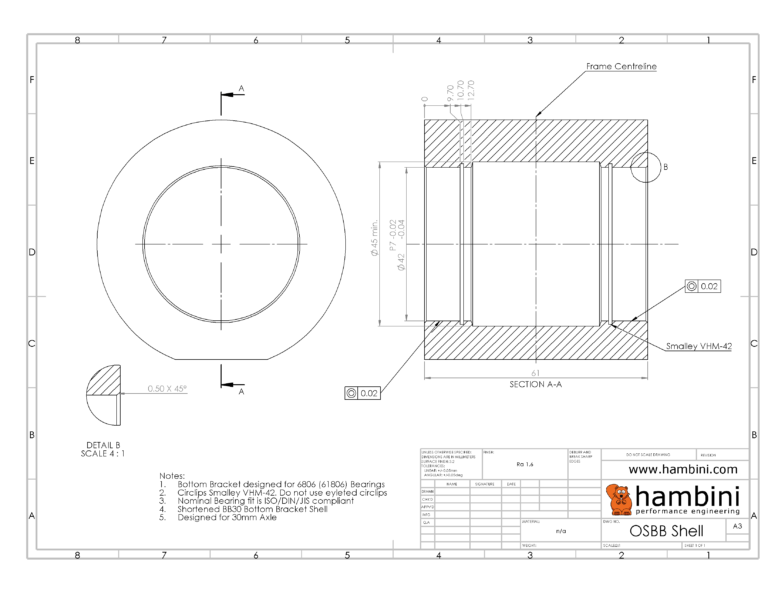

Kerin’s testing setup is riddled with critical flaws that severely undermine the credibility of his findings. He employs multiple uncalibrated TACX turbo trainers at clamped loads, attached to various bike frames driven by reduction gearboxes through flexible couplings. The retained drive-side crank arm introduces a fundamental imbalance in the drivetrain, immediately compromising the test’s validity. Additionally, the drive motor and gearbox are precariously positioned on unstable bases, one on wheels and another on unsteady legs. Neither of which are securely fixed to the bike frame or the floor, allowing for excessive movement and misalignment. The motors themselves will have some element of slip, and the use of multiple different frames further compounds the inconsistency of the tests. This chaotic setup introduces significant variability, making any results highly questionable and unreliable.

In essence there is no repeatability across the tests because:

- The Bike Frames are different (the stay length is unlikely to be uniform)

- The Test cranksets are different, FSA and Shimano are pictured (the imbalance will be different across bikes)

- The motor drive units are neither calibrated nor installed similarly

- The rear mechs are not consistent, Ultegra and 105 are both used.

- The chain tension on each bike will be different

Video evidence of the setup shows the claimed12 kg motor visibly vibrating due to the imbalanced forces in play. Such instability introduces unrepeatable errors even before the testing begins, making it implausible to measure the minute variations in wear (friction) that Kerin claims to detect. The overall lack of control and precision in the setup undermines any claims of accuracy and repeatability, raising serious concerns about the legitimacy of the results.

Industry Experts Raise Concerns

At a recent power transmission event, representatives from two large chain suppliers, Sedis and Renold criticized the chaotic test setup used in Kerin’s experiments. Concerns were raised about repeatability and errors in combination with the unbelievably accurate metrology equipment (see below). They highlighted that this configuration inherently favours lubricants with good damping characteristics, such as those using immersed wax lubricants. Wax reduces wear by minimizing chain vibration and prevents dirt and debris from embedding into the links, as the continuous wax layer leaves no pockets for contaminants to settle.

However, both representatives, who are avid cyclists pointed out that the test conditions do not accurately reflect real-world cycling. In Kerin’s setup, the chain remains on a single pair of cogs, failing to simulate the lateral forces and movement involved in actual gear shifting. In real riding scenarios, gear changes would cause the wax to flake off, significantly reducing its claimed longevity and effectiveness. The representatives argued that this critical factor is entirely ignored in Kerin’s testing, which skews the results in favour of immersed wax-based lubricants. A drip type wax such as squirt would likely give similar levels of friction.

They also pointed out that the inconsistent chain tension and differing rear derailleurs across his three different bikes would make the results largely unreliable and effectively meaningless.

Practical Implications of Lubricant Performance

The representatives from Sedis and Renold emphasized that any perceived performance advantage of waxed chains over properly formulated drip lubricants is minimal, if it exists at all, in real-world conditions. They noted that any potential benefits of wax are largely negated by the inconvenience of frequently removing the chain for immersion – a cumbersome and time-consuming process that most cyclists are unlikely to undertake. In contrast, drip lubricants offer far greater convenience, as they can be easily reapplied without dismantling the drivetrain. One representative even suggested that motorcycle chain wax could deliver 90% of the benefits of a full wax treatment, without the hassle and at a fraction of the cost.

Ultimately, both industry experts stressed that while immersed wax lubricants might excel in controlled testing environments, such results do not always translate to everyday cycling conditions and are largely affected by the rider’s local climate and shifting patterns. They argued that test setups failing to account for real-life factors such as gear shifts, chain flex, and wax flaking are unreliable predictors of a lubricant’s performance on the road. One estimated that under certain conditions, 50 kilometres of real-world riding would be sufficient for a drip lubricant to surpass the efficiency claims of immersed wax, occurring even sooner with frequent cross-chaining.

Both representatives emphasized that maintaining chain cleanliness is the single most crucial factor in achieving low friction and optimal performance. They argued that no lubricant, regardless of its properties, can compensate for the increased friction and wear caused by dirt, grime, and debris buildup on the chain.

To ensure the best possible friction performance, they advocated for deeper cleaning methods, including ultrasonic cleaning and the use of specialized solvents designed to thoroughly remove contaminants from every part of the chain without attacking or corroding the metal. Ultrasonic cleaning, in particular, is highly effective because it uses high-frequency sound waves to agitate and dislodge particles that traditional cleaning methods might miss, ensuring a deeper clean that minimizes friction.

They also highlighted the importance of regular maintenance routines, including periodic degreasing and re-lubrication, to prevent the accumulation of dirt that can degrade the chain’s efficiency over time. According to these experts, a clean chain not only reduces friction but also extends the lifespan of the chain and drivetrain components, ultimately providing better performance and value for cyclists.

Their stance challenges the common misconception that a specific lubricant can singularly transform chain performance. Instead, they argue that the real key lies in a diligent cleaning regimen that ensures the lubricant—whether wax, wet, or dry—can perform at its best in a contaminant-free environment. The representatives underscored that investing in proper cleaning tools and techniques is far more impactful than relying solely on lubricant choice when it comes to minimizing friction and maximizing efficiency.

Fundamental Flaws in Measuring Chain Wear to Presume Friction

Additionally, both representatives highlighted a critical flaw in Kerin’s methodology: his assumption that chain wear can be directly correlated to friction. Even his email signature implies a close connection between the two “…saving you watts of friction…otherwise eating your drivetrain”. The reality is that a lubricant can demonstrate low friction yet still perform poorly in wear tests, particularly if the testing setup is biased toward a straight chain with high damping characteristics, as seen in Kerin’s rig. This fundamental misunderstanding undermines the validity of his test results and casts serious doubt on any claims made regarding lubricant performance based on this flawed approach.

A closer look at ZFC’s Testing Results

Kerin proudly boasts in his email signature

ZFC conducts the worlds most exhaustive independent testing to find and stock the best in class products only, saving you watts of friction that are otherwise going into eating through your drive train components faster.

A contentious statement that is far from the truth. He regularly claims to do testing on behalf of other manufacturers with suitable NDA’s in force.

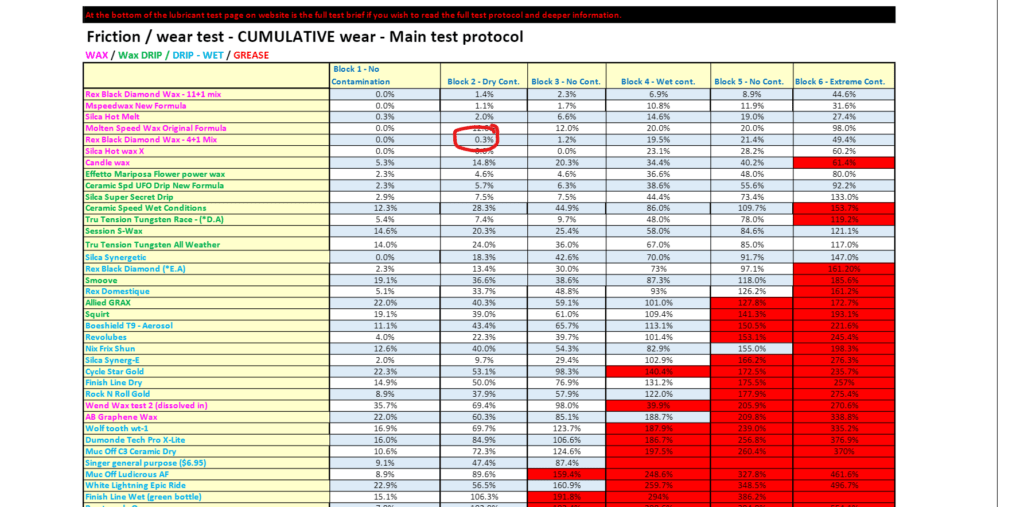

Kerin’s testing methodology is based on a wear tolerance of 0.5%. On his charts, 100% equates to reaching the full wear tolerance of 0.5% chain elongation, while 200% indicates 1% chain elongation. To put this in absolute numbers, Kerin employs a KMC digital chain checker to measure wear. For a 10-link section of a chain with a 1/2″ pitch, the nominal length is 127 mm, and 0.5% wear corresponds to a 0.64mm extension. **The test section length is unknown but appears to be 10 or 8 links; the numbers will scale in any case.**

Kerin’s KMC chain checker is essentially a modified digital vernier caliper with jaws adapted to interface with the chain rollers. After consulting with two retailers, it appears the tool does not come with a calibration certificate or setting standard, and it’s claimed accuracy is 0.1mm, the screen displays measurements to 0.01 mm.

Kerin claims that his testing can detect a measurable difference of 0.3% of 0.64 mm – equating to 0.0019 mm (2 microns). However, these results are 50 times more accurate than the stated accuracy of his uncertified and uncalibrated measuring equipment, which has a claimed accuracy of +/-0.05 mm. Even a Mitutoyo caliper, the benchmark in industry, has a certified accuracy of +/-0.02 mm, which is still far less accurate than the accuracy Kerin is asserting. This does not take into account the level of user error associated with such devices either which will reduce their precision.

When extrapolated over a full chain length of 116 links (approximately 1.47 meters), he asserts that his setup can detect a variance of just 0.22mm (the thickness of 2 sheets of paper) on a chain that is inherently flexible.

To put this into context, Kerin is claiming his measuring equipment can detect the presence of a single rod of E-coli bacteria (2 microns) on the bike chain over 10 links.

Conclusion

Kerin has expressed reluctance to adhere to established engineering principles, choosing instead to develop his own testing methods that align with his business interests. While he claims to be “independent,” selling products while asserting independence presents a conflict of interest. It appears that his testing is used as a promotional tool to enhance his credibility and encourage potential buyers to trust his results.

Despite stating that his work is a hobby and that he could shift to something else at any time, his actions suggest a strong focus on marketing products that can be quickly sold, sometimes at the expense of thorough engineering research. Rather than contributing to genuine knowledge, this approach seems primarily focused on crafting a narrative that maximizes sales. His disregard for established industry standards and best practices raises concerns about his commitment to the rigorous processes required for reliable, credible engineering.

Concerns have been raised about Kerin’s technical knowledge and expertise, with instances suggesting a limited understanding of fundamental concepts. His lubricant testing setup appears to lack precision, repeatability, and proper controls, which undermines the credibility of his findings and casts doubt on the validity of any product performance claims he makes.

This apparent disregard for scientific integrity and sound engineering principles is a significant concern. Kerin seems more focused on marketing than on providing consumers with reliable, verifiable information. His testing methods and conclusions should be approached with caution, as they are based on unverified procedures that appear to be designed to support his narrative rather than reflect real-world performance.

The disorganised nature of his test rig, combined with the precise results he claims to measure are contradictory and to put it bluntly, unbelievable.

I’ve always had my doubts about ZFC. It never really added up for me. Honestly, the test rigs looked like they were cobbled together from whatever scraps they could find at the local junkyard. Hardly the setup to inspire confidence.

And his comments about not wanting to read that book? Alarming doesn’t even begin to cover it. Keeping that quiet was the real plot twist!

I got fed up of listening to people use his work as if it was gospel. It was time someone said something.

To Hambini, the man himself: You clearly understand that the most effective way of spreading misinformation is to lace it with enough truth to gain credibility. You are an expert in this technique. In the world at large, it is the basis of so many attacks on reasonable scientific understanding. It causes paralysis and disfunction in cases where there are obvious solutions that we should be pursuing.

You could use your intelligence to illuminate the big picture and provide a voice of clarity amidst the confusion. Instead, you often weaponize information towards personal vendettas and for general self-aggrandizement. This is why so many people don’t pay attention to the information you peddle. One can never tell which side of the pitch you are playing on! Is he working for good? Bad? Sensationalism at the expense of illuminating the real issues?

Are you satisfied with your role in the world? I see a smart person with a lot of wasted potential, who could be doing far more good in the world.

[PS: I agree that what comes out of Adam’s mouth is not gospel and not always perfectly. But that is, again, focusing on the details, at the expense of the larger picture.]

[PPS: I give you credit for allowing dissenting voices in this forum, even if I disagree with your seeming intentions and goals on a number of issues.]

Get a degree in Mechanical Engineering if you don’t understand the big words mate…

Adam Kerin’s honesty is seriously questionable at this point. The results he’s showing? Honestly, they’re laughable, like you’d expect something more solid from a kid in 10th grade. It’s pretty obvious he’s more interested in pushing products then offering anything of real value. And let’s not forget his outright refusal to read the appropriate books on the subject. I still can’t believe it. It’s almost like he’s afraid of actually getting informed. What’s really scary tho, is how much influence he’s managed to build up with such shaky work. Wow, thanks Hambini for enlightening me on this mess. Just goes to show how hype can easily beat actual substance.

I mean, the dude’s about as sharp as a rolling pin. Honestly, I’m stunned you managed to keep it so damn civil, especially given all the racist crap he’s been spewing over the years. You’d think with a brain like his, he’d lay off the BS, but nah, typical copper. Can’t expect much more from someone who probably thinks duct tape and WD-40 can fix a jet engine.

could you (approximately) quote the racist part? i watch the guy and while i have a healthy dose of scepticism for his testing technique, i have yet to hear anything remotely racist from him.

Hambini has been quite civil. When ZFC broke his arm, Hambini actually went on his Instagram and said something like, “I hope you get better soon; I know we have our differences.” On the other hand, Adam has been calling Hambini a “creature” repeatedly, and there are multiple sources saying Kerin said he should be “curry bashed.” Considering all of this, it’s surprising how composed Hambini has been.

thanks. that isn’t great, is it

Absolutely false. Rumours spread by a has-been (and known liar) local vegan numpty.

‘I know exactly what I should sell’, and that really says it all, doesn’t it? If he’d done the actual work, he wouldn’t look like such an idiot now. He just looks like a complete fool.

I was living a life of general ignorance and thought his work was kosher before this. The chain checker is the icing on the cake! The bit about ecoli was brilliant.

The Dunning Kruger effect is strong in this one..

He is in over his head.

Being a layperson (ignorant sod) concerning engineering, I truly appreciate the depth of your explanations. I can follow the physics and can google any terms I wish to study further.

Thanks Hambini!

James

My experience is similar to the comments from the Renolds chain guy. I’ve found the relube time to be much shorter than any of the manufacturers have claimed.

I did follow Adam’s youtube channel before reading this and I will probably continue to do so but with increased scepticism. I had an open mind beforehand and thought Hambini was stirring but it appears not. I do feel somewhat cheated. He did portray himself as some independent guru but it is obvious now he is not. I’m very disappointed.

Has anyone noticed Adam gulps periodically when he’s talking. It’s the sign of a liar.

I don’t things an evil liar tbh – just a guy who tried to make a business out of what he considers common sense… but the world is full of evidence that common sense is often bs.

Regardless of his engineering, he’s clearly excellent at business and marketing! He’s spent very little money, has a huge following of people who spread his message via word of mouth for free, and he makes very nice margins on the products he sells.

The test data is evidently made up as if he can measure to 1 micron with that device. It looks like it’s from Aldi

Adam Kerin, the Racist Clown.

Awesome and on point as always! Great explanation of what happens when a little bit of knowledge is dangerous – this needs to get wide circulation and the companies who pander to him should be called out also.

Hallelujah. At last! This monster really did need to be reviewed and published by someone with genuine technical ability. If elongation is the parameter used to indicate wear then all chains need to be treated as equal – cleaned thoroughly before lubrication and after testing. Leaving large amount of wax in situ before measurement does not allow full elongation. Hence some chains seem to record negative wear.

Adam does work incredibly hard and has invested massive time and effort into this project. He has created a huge amount of support and a lot of data. This attracts the content creators in cycling media who need to publish, and the brands who need to independently certify their offerings.. However the truth must come out eventually, and agree that in his work there is an apparent disregard for scientific integrity and sound engineering principles. Wax is not the messiah.

I am appalled at reading this. If you are in it for the money, you have a responsibility that goes with it. What a prick.

It says a lot about the industry as it has taken this long to call out the shoddy testing of this moron. Silca refer heavily to his testing, what do they have to say about it?

Josh from Silca is the other waxed chain spam creator

I’m a scientist (physiology and biophysics), not an engineer. I personally find immersion waxing to be a great solution for my riding conditions (Houston, not the UK). I rarely ride in wet conditions. I also know how to read so I am aware that Hambini is not criticizing wax as opposed to some other lubricant method. I find his critique of these so-called testing procedures to be essential reading and overdue. It is as close as we can get to peer review in this space. And it is very convincing to me. Essentially this guy’s testing is meaningless. It should be irrelevant to how you choose to care for your chains.

He sure know’s how to talk the talk. But if your gonna throw out half-assed testing with them shoddy methods, someones gonna tear you apart. I’m shocked it took this long!

Why has nobody questioned his methods for so long? It looks so obvious now Hambini has highlighted it. A controlled test on 3 different rigs. WTF

He provided data when there was an absence of data.

In that scenario quality of data doesn’t mean much.

Well, I don’t care about the ceramic stuff, but I do find the chain tests interesting; and some of your comments petty:

Most importantly regarding chain elongation: He does give more details about chain wear measurements in a fairly unclear pdf [1]. But he does measure the whole chain, and claims to be accurate to 0.2mm by comparing with a new one. Certainly challenging, but not ridiculously impossible?!

Durability vs efficiency. Again, he’s open about both not being equal [2]. But drivetrains are certainly faster if they are not worn…

“Industry experts” arguing his methodology isn’t 100% replicating everyone’s riding style & environment. Surprise! You don’t collect that much data without a simplified test setup. Is there anyone publishing better data? I don’t think so, because I don’t think anyone does better tests.

And lastly… “in radians per second), not simply RPM” Are you fucking kidding me? He didn’t even say “watts” but “power”, so complaining that he doesn’t use your favorite units makes the whole post seem like a joke.

Granted, I’m a theoretical physicist setting all units to 1 if possible…

Also “power cannot be measured directly”… do you want a philosophical debate about what is and isn’t direct? How do you even measure force or mass “directly”, without distances or currents, or…? Unit systems are just choices there’s nothing fundamental about them.

0.2mm is 2 sheets of paper. On something that is 1.4m in diameter, that would be a decent runout number. On a chain that is flapping, I’ll wait to see how he measures it but I call BS.

The difference between people in industry and Adam Kerin is, the people in industry have qualifications and basic engineering understanding. Adam has neither and has learned by googling. That will get you so far but it’s quite easy to rip holes in his testing.

Mechanical Power is measured in horsepower or Watts. If you can think of another unit, then do let me know.

It’s quite obvious that you are a theorist.

Some of your criticism is based on his videos and pictures from his test rig.

I guess that means you are sharing videos and pictures from your own aero wheel testing now?

If you want to pay the engineering consultancy fees, then you don’t have to stop at pictures; you can have video, too.

> Mechanical Power is measured in horsepower or Watts.

> [power] must always be calculated and is typically timed.

Hm…? Either way quantity != unit. And I’d prefer geometrodynamic units over horsepower.

> On a chain that is flapping, I’ll wait to see how he measures it

I’d think the chain will stop flapping if you tension it… Thing is, the 0.3% is the least interesting number in this chart. If there’s a 0.6% error on it, that’s still fine by me. The relevant numbers are probably in the >10% regime, and even I could measure that.

> That will get you so far but it’s quite easy to rip holes in his testing.

Okay, but then do a better job at it. I used to spend time in the lab, too, thinking about error sources, estimating and reducing their impact. I find it hard to believe the points you raise matter too much:

> The retained drive-side crank arm introduces a fundamental imbalance in the drivetrain, immediately compromising the test’s validity.

That’s another joke, right? The imbalance at 100rpm or whatever… Good thing my pedalstroke is perfectly round.

> […] excessive movement and misalignment. The motors themselves will have some element of slip […]

So what, the chain won’t notice that, and only the output power is measured…?

> The chain tension on each bike will be different

You made this point several times (stay length & rear mechs), but how much of a difference do you think that actually makes?

The chainring probably exerts about 200N to 1000N force, while the tensioner is probably more on the order of 10N? It’s a source of error, but doesn’t seem significant to me.

> Concerns were raised about repeatability and errors […]

He mentioned repeated tests with about 5% relative error, iirc. I’m sure he’d tell you (a lot!) more if you asked him.

> Wax reduces wear by minimizing chain vibration […]

Seems fairly relevant for my off-road riding?

> In Kerin’s setup, the chain remains on a single pair of cogs […]

Actually gearing is changed throughout the cycles, see previously linked document.

> gear changes would cause the wax to flake off,

That’s just nonsense, there are plenty of people riding waxed chains in the wild. The lifetime of the wax treatment is not significantly reduced by changing gears.

> A drip type wax such as squirt would likely give similar levels of friction.

He tests those, too.

> drip lubricants offer far greater convenience

> they advocated for deeper cleaning methods, including ultrasonic cleaning and the use of specialized solvents

Guess you can’t have it both ways, right?!

There’s no way that guy can accurately measure 0.2mm over a 1.4m span, even with added tension. The more tension he adds, the more the chain will deform and stretch beyond its intended limit.

Hambini’s point about vibration is spot on. The motor alignment is inconsistent, leading to unpredictable random vibrations, which is obvious in the video footage. Don’t underestimate the impact of that vibration; it will cause internal wear on the chain, something you wouldn’t see in a perfectly aligned and balanced setup, even if the torque application is peanut shaped.

Hambini highlighted valid sources of error, which you’re dismissing as irrelevant. They might be insignificant for major length changes, but we’re talking about 2 microns here. The guy’s test seems overly optimistic, most would call it garbage, and I’m with Hambini on this one; it feels like it was done just for publicity.

But he’s not measuring 0.2mm over 1.4m, he’s comparing a new chain to a used one. It’s just a relative measurement, so seeing sub-mm differences is certainly possible.

> […] but we’re talking about 2 microns here.

No, we’re not; He could’ve written 0% in that field, and that wouldn’t change the interpretation at all.

The question isn’t “is his setup perfect”, but “is he seeing the same leading causes of chain wear as you do on/off-road”. My chain is slapping around a lot more when I’m gravelling, but I struggle to believe that the vibrations cause more wear than contamination through dust and mud.

This is a response to Leo’s message since the thread doesn’t allow for further depth.

0.2mm is a fixed measurement, whether it’s relative or not. It’s 0.2mm over 1.4m, and even if it were 1.41m, the primary dimension remains unchanged.

It seems like you’re finding every possible excuse to cover for the shortcomings in his testing.

@Matt

People have compared chain lengths by hanging before, if you google something like “Bicycle Chain worn out different length” you’ll find an image of a very basic setup on wikimedia commons, where you would be able to read off about 0.5mm _difference_ between chains.

If you build an improved setup and tension the chains with the same force, improving the accuracy by a factor of 2 just doesn’t seem all that impressive.

Now, to what extend contamination or wax in the rollers affect your measurement; That’s a relevant question. Maybe there’s some bias. I just don’t think that will matter too much at later stages of the experiments.

> It seems like you’re finding every possible excuse to cover for the shortcomings in his testing.

Every test / experiment has imprecisions, shortcomings, and errors. Adam maybe doesn’t do a fantastic job analyzing the error sources scientifically. But it’s still the best, fairly realistic data pool anyone is making public. And it does help cut through some marketing BS, which I appreciate.

His 0.2mm bike chain accuracy claim is ridiculous. He’s got a better chance of measuring the diameter of toothpaste.

That’s brilliant!

Well that’s me done every time I clean my teeth.

“what are you doing?” Me- “wondering about the diameter of my toothpaste!”

In classic Hambini style, far too much time spent on pedantry, pettiness, and personal attacks rather than using his ‘expertise’ to provide actually useful advice.

To some extent, ZFC’s practices are irrelevant. Ultimately, the main question everyone wants answered is “What’s the best method of chain lubrication?” Does Hambini help us make any progress towards answering this question? Inadvertently, perhaps he does.

Everyone agrees that a clean chain is best:

Section 4.3 paragraph 3

“Both representatives emphasized that maintaining chain cleanliness is the single most crucial factor in achieving low friction and optimal performance”.

Section 4.3 paragraph 5

“According to these experts, a clean chain not only reduces friction but also extends the lifespan of the chain and drivetrain components, ultimately providing better performance and value for cyclists”.

My understanding is that immersive waxing is better than traditional lubes at keeping chains clean. Surely this is evidenced from the fact that you can grab a chain that has been immersively waxed and come away with essentially clean hands. We all know how that goes if you try it with a chain that has been traditionally lubed. Hambini even acknowledges this to some extent:

Section 4.2 paragraph 1

Wax reduces wear by minimizing chain vibration and prevents dirt and debris from embedding into the links, as the continuous wax layer leaves no pockets for contaminants to settle.

Okay then, what about the process of cleaning the chain?

The ‘industry experts’ seem to think that popping open a quick link and throwing your chain in a slow cooker to rewax is far too complex and time consuming for us non-experts. Yet, if you use traditional lube, they recommend deep cleaning your chain with an ultrasonic cleaner. I’m not entirely sure how that is any easier, cheaper, or faster than immersive waxing?

Section 4.3 paragraph 4

To ensure the best possible friction performance, they advocated for deeper cleaning methods, including ultrasonic cleaning and the use of specialized solvents designed to thoroughly remove contaminants from every part of the chain without attacking or corroding the metal. Ultrasonic cleaning, in particular, is highly effective because it uses high-frequency sound waves to agitate and dislodge particles that traditional cleaning methods might miss, ensuring a deeper clean that minimizes friction.

It might help if you read the first parargraph of this article.

And you should perhaps read the rest of it then. The first paragraph is a lie.

Yeah, I’ll cop to it. I got roped into the whole ceramic bearing craze thanks to ZFC. Grabbed some HSC ceramics from Adam, and they carked it in about two months. Switched back to SKF and never looked back since.

ZFC’s a dodgy fly bynight outfit

Idiotic, defensive chain wax enthusiasts rush in to defend their idol, only to watch him get dismantled by a real expert.

‘“Torque (turning force) x RPM = power.”

This statement is fundamentally incorrect. Power is calculated as the product of torque and angular speed (in radians per second), not simply RPM.’

Lots of interesting points here but if you’re going to be picky, best to be right about it too.

RPM is a measure of angular speed, it’s an angular displacement (where 1 revolution = 2pi radians = 360 degrees) divided by time. You can convert the SI version of angular velocity, radians per second, to RPM just by dividing by 2.pi and multiplying by 60.

That aside, Hambini is always worth reading – his stuff makes you think and that’s a good thing. It’s especially good to see some rigour about measurement methods and tools.

This sad little essay reeks of desperation and embarrassment on Hambini’s part. I feel bad for the guy!

Back to that embarrassing essay by Hambini:

1) Chain elongation can be measured. It doesn’t take an engineer to do that job. A 0.5% worn chain is obviously longer than a new chain. You can hang two chains on a nail and see the difference in length from across the room!

2) It would be ridiculously easy to see if the different test setups were producing greatly different results: Put the same chain model on all of the test platforms, use the same lubrication method, and measure chain wear after some distance. Even Hambini could figure out how to do that! If the differences in test setups are small relative to differences caused by different lubricants, then all of this hullabaloo about derailleurs and chainstay lengths amounts to a hill of beans. It would be a small amount of noise relative to the overall signal.

3) When it comes to chain wear, the difference between high and low performance lubricants is large and obvious. A chain that is toast in under 1000 miles of gravel riding (typical wet lube, wipe off, reapply method) vs >4000 miles (throw chain in the wax pot every 150-200 miles) is obvious in the real world. It’s obvious in these tests, too. (Again, I feel bad for Hambini. This is just embarrassing!)

4) Adam Kerin can’t stop talking about the fact that a clean drivetrain is what leads to longevity, whether it is wax or wet lube. That’s exactly what Hambini’s industry experts say, too! So, Hambini is not rebutting anything. He is merely restating what Adam Kerin keeps repeating: If you can remove most of the contamination between rounds of lubrication, you will greatly extend the lifespan of a drivetrain, whether that’s using a wet lube or a dry lube.

5) We are talking about a chain running through a bicycle drivetrain. Hambini is the one who is over-complicating it. Adam doesn’t claim his results are equal to real world riding. Adam claims that that the treatment lifespans he sees (e.g., single treatment longevity) are highly optimistic because real world riding a much messier. Hambini merely echoes Adam’s own point!

6) All lab tests will be over-simplifications compared to real-world conditions. That’s the nature of laboratory testing. Every model is wrong, the question is whether that model is useful. Given the strong link between what we see in these tests and what we can observe in terms of real-world chain and drivetrain longevity, it seems like a useful test.

7) Adam states over-and-over again that drive train wear is an imperfect proxy for efficiency. Who exactly is Hambini arguing with by stating the same thing!?

Overall: Hambini sounds like a child trying to use big words to mask his own insecurity.

Or maybe Hambini is a brilliant guy who knows how to stir up false controversy and turn that into dollars!? Maybe I’m the one who is being trolled by thinking he is writing this nonsense with sincerity!

*** Well-played Hambini. Well-played! ***

He’s claiming to measure 0.3% of 0.5% which compounds to 0.0015%

[To Start: I don’t think that ceramic bearings provide meaningful value, relative to their cost. I have not evaluated Adam’s claims regarding them, so I don’t have anything to say about that topic. Based on the available data that I’ve seen, lubricants and seals play a larger role in frictional losses than the bearings themselves once the bearings are of reasonable quality. Back to the main thing I’ve seen Adam focus on recently: chains and lubricant testing.]

Hambini’s essay is the typical throw-the-baby-out-with-the-bathwater attack that we often see online. He takes imperfect but useful information and declares it useless. And then personally attacks the person producing that information, rather than providing a helpful, big picture look at whether the results are meaningful or helpful, despite their flaws.

It’s clear from Adam’s (way-too-long and poorly edited) videos that he doesn’t claim to dance on the head of a pin with regard to testing accuracy. Nor does he claim that his simple testing method is perfect. From what I see, he readily acknowledges that small differences should be considered within testing error and he focuses on the big differences in his recommendations.

This essay exemplifies Hambini’s art of taking the big picture (e.g., an amateur who is trying to bring us some independent testing, which is imperfect, but useful) and instead focusing on the small, petty, personal, and vindictive. Yeah, Adam is not the world’s foremost technical guru. I think we all know that. He knows it, too. I haven’t not seen him claim anything to the contrary.

In a world where most technical product testing and knowledge is locked behind corporate doors — and customers only see what comes out of the marketing department — we need more independent testing. We also need to understand when that testing is useful — or misleading. Hambini doesn’t seem to have an interest in making that distinction in this particular case. He’s decided to instead focus on minutia in an attempt to personally attack someone. Losing the forest for the trees, as the saying goes.

Examples of highly imperfect, but still useful testing data, in places where consumers had none previously:

Bicycle Tires: All we had before BicycleRollingResistance was marketing claims and magazine article writers, mostly with liberal arts degrees, telling us whether tires “felt” fast. Or if we were lucky, the German magazine Tour might test a few tires occasionally. Are BRRs tests perfect? Heck no! Only a single tire sample (instead of 3+ tires obtained from different batches)? Not good. Is a steel drum equal to real-world riding on roads? Heck no! That said, if a tire has very low rolling resistance, it will show up on the drum test. Same for a tire that has very high rolling resistance. But understand that tires that are within several watts of each other cannot be distinguished as different in these tests. And there will only be a general correlation (far from 1:1) between testing on a steel drum and riding on variable road surfaces. If we supported this sort of independent testing (instead of, for instance, doing Hambini-style takedowns), then maybe we could have a more professionalized process with lots of replication, better measurement of experimental error, and better data collection methods.

Chain lubricants: There are lots of terrible lubricants with impressively misleading marketing claims. Are Adam Kerin’s tests perfect? Far from it. That said, if one lubricant causes a chain to wear 4 times faster than another in this imperfect setup, can we say something useful here. Absolutely. Similarly, are Adam’s tests going to give us a perfect ranking of which lubricants are fastest? Definitely not. He’s testing chain wear, not frictional losses. He keeps saying that (over-and-over again). Is there some rough correlation between these things at a high level? In many cases, yes, but that correlation is far from 1:1. Again, he readily admits these limitations.

As someone who works in a scientific/technical area (and yes has the degrees and has read the books in my own field), I recognize that the question is not whether a test, or the person conducting the testing, is perfect. It’s whether: 1) the test is useful, and 2) how much uncertainty is contained in the results. It seems likely that Adam’s test are useful for finding large differences between lubricants. That’s a win for consumers, who had no data previously, aside from Friction Fact’s original testing results and other random bits of information.

Imagine a world where Hambini did something useful here, like sit down with Adam and help him improve his testing setup, help him measure where the largest sources of error might be hiding, and figure out how to streamline the testing (and increase repeatability)? That would help cyclists and consumers. Instead, we get hate, vitriol, and pettiness that does a disservice to everyone.

*** Okay: Now everybody can go back to their petty, vindictive, and unwarranted personal attacks, exactly as Mr Hambini would have wanted. REMEMBER TO FOCUS ON THE MINUTIA! And ignore the big picture. And to be as personal and vindictive as possible. REMEMBER TO SEE NEFARIOUS MOTIVES around every corner. Hambini would want it that way! This is a REAMING after all! 0.0015%! REMEMBER TO MENTION THAT NUMBER! Clearly that’s the main message that ZFC is pedaling. Ignore the bigger picture. And don’t forget to add some nasty name calling! ***

Best Comment!!! I like both ZFC and Hambini.

TLDR

1) Kerin couldn’t be bothered to purchase technical standards and expected them to be spoon-fed to him.

2) He disregarded advice from Hambini and HSC, who both said ceramic bearings are terrible for vibration.

3) Kerin can’t distinguish between brinelling and false brinelling.

4) Everyone agrees that keeping a clean chain is key.

5) Kerin claims he can detect bacteria on a chain link.

6) Hambini believes Kerin’s tests are just a publicity stunt to sell more products.

7) Kerin’s tests lack consistent controls.

8) Kerin claims it’s just a hobby, but he’s hired someone for it (my addition which is kind of odd).

Kerin is just the unqualified illiterate mouthpiece of Josh Poertner that well known fat CNUT who dyes his hair badly and tries to sell overpriced crap pots for $100 when you can get the saem thing on Amazon for $30. He doesn’t even have an engineering license and is not a Professional Engineer (P.E). You can check on mylicense.in.gov/everification.

I had my suspcisions when Josh seemingly without hesitation started quoting ridiculous decimal levels of accuracy. The guy is a fraud and he has people sucking from his tea spoon.

Kerin is Poertner’s puppet or rentboy.

I can’t agree you more, mate!!

Why does everyone seem so hung up about the “this is only a hobby” point? How does this affect Adam’s credibility in any way? It just seems like childish name calling to me.

Also, doesn’t exactly the same thing apply to Hambini?

From their YouTube page:

“Zero Friction Cycling is now the worlds most referenced independent test facility for lubricant and chain performance. Our test facility has conducted over 300,000km of controlled testing and now with a new expanded test facility, this is expected to grow by around 200,000km per year.

Zero Friction Cycling is used by the many of the worlds best lubricant manufacturers to put their lubricants to the test as well as testing during development. Our test facility uses the test data to lead product selection, only genuinely proven top products are stocked by Zero Friction Cycling.”

He claims to run it like a lab; look at our controlled testing; it’s a back street garage.

A joke… Cops are all bent.

I’ve had my doubts about Adam. He’s the kinda guy who’d write a 2hr speech about something as pointless as takin a dump, and he just comes off sketchy, gulping down every other word like he’s nervous. it’s wild that people didn’t even notice he couldn’t be bothered to pick up a book to learn more and was just focused on what he could hustle and his rampant spreading of misinformation that has gone unchecked.

I’ve dealt with Hambini plenty of times, and he ain’t nothin like his YouTube persona. He’s super professional and really knows his shit. he’s advised me to leave the bottom brackets in and not try to sell where he could have easily done so. I’d trust a Eurofighter engineer over some wannabe salesman any day.

Thank for this. Pretty much confirmed most of what I thought about this fellow after a few email exchanges questioning his expertise and methods. He quickly resorts to insults and personal attacks when challenged. After he made some claims about a particular brand of lubricant I asked about, including some implications that he’d been in-contact with company, I emailed the company directly who claimed they’d NEVER been contacted by him. So much for credibility IMHO!

While I have my own opinions about the “wax-cult” that has existed long before ZFC, he seems to be a semi-clever opportunist cashing-in on the expensive products being marketed to cult members vs melting paraffin in pots on the stove from back-in-the-day.

My main problem with ZFC is that I never know what the results are, because it is impossible to get the end of a video without nodding off.

Someone teach the man some brevity, please.

A man clearly in love with the sound of his own voice. I laugh each time he comes on saying he’s too busy to make a long video this time because, blah, blah…and they blathers on for a hour + Does he get paid by-the-word?

Technical inaccuracies, a half baked test scheme and a ceramic vs steel bearing pdf that even his suppliers don’t agree with. He’s then on record saying it’s a hobby whilst employing some guy called andrew to do his retail. Such nonsense.

This clown needs his vocal cords removing, he can talk for hours about shit. It might stop the knut from gulping so much.

I don’t belive in Adams he is non academic and has en’t got any knowlegde at al but there is some claims where he is right, mostly out of luck tho. i dont think he could red an academic paper (lets say this is not uncomon because i wouldn ‘t say most graduate students could understand whats written in them too)

but remember, even a blind chicken may find a corn!

here are some documents that kind of suport adams claims.

https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/abs/10.1098/rspa.1922.0017

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11665-020-04789-8

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0043164898002348

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0927775722016843

https://asmedigitalcollection.asme.org/fluidsengineering/article-abstract/doi/10.1115/1.4061477/1197790/Special-Experiments-With-Lubricants?redirectedFrom=PDF

https://pubs.acs.org/doi/pdf/10.1021/ie50017a001

yeah some of them talk more about liquid parafine witch is common in higher temperatures but there was never a claim about temperatures made ever, but also we know, to a certain degry that in a simplyfied world $ pV= k_{B} N T $ please remember thereis no eigenvolume in this and other physis phenomena are kind of ignored but thist holds for nonextreme cases. Also friction generates temperature.

for a full statment not that Under high pressure mankind would certainly prefer Tefflon or molly only sheets (this is more for for sliding preconstrukted bridges in place)

About the upcomming video about Graphene it seems that industries chemist and engeniers are more of the corupted side.

For reference Graphene is a carbon monolayer with indefinite boundarys, and if you ask a physicist its the only aceptable Deffinition no other atoms no other layers and such stuff. Tho it seems that chemist and engeneers would also include some variations of this witch is quite boring https://www.thegraphenecouncil.org/page/WhatIsGraphene

so i ve questions about that. Are all engenners and chemists drunk during there physics classes? didnt they take Solid states Classes?

Please take the time to check your spelling, grammar and generally garbled (and very infactual) text so it is legible and understood!

Interesting article which I thought was well presented.

I think if you’re going to advertise yourself in the way that ZFC does then your test protocol must be beyond reproach, if it isn’t then you can fully expect criticism or doubt with respect to the validity of your claims. If you then choose to sell products on the back of less than ideal testing then it is quite understandable that people may question your integrity.

This guy claimed you needed a special Silca pot ($100) to heat the chain wax when the 15 USD beauty wax heater would do the job.

His levels of credibility are only bettered by the stupid idiots who follow the wax cult that he has started.

in fact u cant read, but thats a you problem.

its not a cult there are some credible things to waxing under circumtaces, see the links above

if u think this rant is about waxing youre like adam, a human witch dossent undersand anything about mechaniks and science. also reading scientific reports is beyond youre mental skill level

this rant is obusly just about the methods used and the mental skill of adam and his claims

if you read the provided papers and the article closely and with mental skill you would know this

He didn’t start it…it’s been around for decades! I can still remember running these wax-cultists out of our bike shop in the mid 1980’s when they wouldn’t stop berating us for selling chain oils. A decade later there was the club guy who bent my ear at a dinner until I changed seats…a guy who later burned down his shop/shed cooking his chains in wax. Friction Fiction’s just made a biz out of catering to …the “Scientology of Chain Lubrication” by selling $50 bags ‘o wax to these cultists who back-in-the-day just used cheap canning wax.

I think a fundamental problem in ZFC’s protocol is the mix/confusion about “friction”, “drag” and “wear”. You might have two rough surfaces made of diamond, that has a lot of “friction”, but it just doesn’t “wear”. You can also have two perfect smooth surfaces made of much softer material that has little “friction”, but just quickly “wear” down. You can’t use “wear” to proxy gauge “friction”.

The first time I read his test I just felt something’s not right… but I just can’t point out where. After this reading it suddenly clicks. I might be wrong because I lack the same engineering background in physical world. Wear depends on a lot of different things, friction just one of them.

I‘m sorry, but did you read any of what you yourself wrote there?

If you really are an even half way decently trained engineer you‘d actually get off your high horse and stop with this nonsense.

I especially loved the section about how time consuming immersive waxing is, followed by you suggesting time consuming deep cleaning methods to use drip lubricants for relubing.

On a popular cycling subreddit people might be asking if this Fred is stoopid now..

If you did read correctly, then you’d realise I was merely quoting what Renold and Sedis were saying. I am (personally) not suggesting anyone wax or use oil.

Do ANY oil-based chain lubricant makers suggest a chain be chemically/ultrasonically cleaned BEFORE their lube is applied? None of the instructions on any chain oil I’ve ever purchased called for such a thing. I’ve NEVER done this, feeling adding oil to the grease already on the chain is just fine. Of course I’m not doing any testing to the point of excluding the factory grease, I just drip some oil on when the chain looks or sounds dry, wipe-off the excess and call it good. Cleaning is a bit of diesel fuel brushed-on followed by washing off with dish soap along with the rest of the bike/drivetrain. This simple, cheap, easy regimen has worked for decades while not putting any $$ into the pockets of charlatans like Mr, Friction Fiction. Chains are cheap, why spend all the time/money fooling around with something designed to be replaced when worn? Simply replace it BEFORE it wears the cogs/chaingrings! Will Friction sue me too now?

Adam loves his own voice, his hambini prelude to reaming was 26 minutes!

This guy is a scam artist, the cheek to say he’s doing it as a hobby whilst he has someone on the books. What a joker.

Well Done Hambini, this type of false advertising needs to be called out.

Let me say it this way. What got me onto the chainwax wagon was less mess (when you live in a flat it makes a big difference); and i will telll you one thing with n=1 teh chain and cog life has extended dramatically. And it might be only the fact that with wax you essentally clean thoroughly the chain every two weeks but i actually found it much less “involved” than you lube representative recommend – ie using chemical degreasers. to sum up my world salad – i switch to wax and i am an example of extended longevity. I beleive the oil industry makes teh whole “taking off the chain” but sounds much harder that it actually is.

PS proposal – maybe we could do real world study – and hear from other people that switched to wax. obviously it will be self reporting but so are voting polls

Setup itself does not matter if you use same setup for all tests. I’m skeptical of ZFC repeatability and sample sizes.

Measuring 0.3% does not matter when error is at least 5%. I just look at whole test, how far it went till 100% wear.

Anecdotally I’ve tried waxing on a road bike and it worked for me. When using oil, I needed to re-lube every 100-200km and every 2-3 rides chain was gritty and needed deep clean. I wore out chain to .5% in ~5k km. With waxed chain i replace it every 500km (or earlier if starts squeaking). So far I’m over 9k km in while rotating 5 chains. Let’s see how long it lasts.

+/- 10% is really good enough for a chain wear test. ZFC’s test are good enough for at least comparing a shitty Muc-Off product to something actually useful, like Squirt or Effeto Flowerpower.

Disgusted to hear that someone has made (now deleted) threats to ZFC’s wife here in the comments. This is shocking and, even if one bad apple is responsible, it shows the toxic culture fostered here and the calibre of people reading the article.

Like yourself?

Didn’t Friction Fiction make some claims one of his critics was involved in online pornography? I know from exchanges with him he’s a nasty fellow when criticized…but isn’t that obvious when he makes a series of zootube videos (now up to 5?) attacking Hambini? For a guy supposedly so busy testing and selling his products HTF does he have the time to make all the video rants? Seems a bit of a kook IMHO.

ZFC’s tests, as rough as they may be, are the first product-to-product chain lube comparison that the internet has ever seen as far as I know. A few thoughts: wet lubes intuitively are going to be a problem in dirty environments. Waxing, on its face, seems like a sensible approach to keeping dirt and contaminants out of the rollers and links. Having tried a lot of lubes over the years, a drip-waxed chain stays quieter and cleaner than a wet-lubed chain. And a lot of people are observing that waxed chains (immersive in particular) are lasting a LOT longer in real-world use. The ZFC tests are consistent enough between products that even without full-on engineering methodologies, we’ve got a battery of tests that will put each lube through a series of test whose results are meaningful and useful, and scores of riders around the world are having similar results. If the scientific method is really getting badly abandoned in Adam’s lab, it’s up to someone to put together a test protocol, don the white coat, and get it done. ZFCs tests, rough as they may be, are at least providing guidance to cyclists to products that will enhance the life of their chains. It’s a win, even if it’s ugly.

“…wet lubes intuitively are going to be a problem in dirty environments.”

OK, but the question is how dirty and how often things are cleaned rather than wax vs oil. I can see wax having big-time benefits if you are lubing something like steel tractor “belts” (for lack of a better word) that spend a LOT of time in/under soils, but a bicycle chain in normal use is quite different.

I’ve never looked closely at Friction’s test protocol but I’m thinking there’s a part where dirt/soil is dumped onto the chain. Is that correct? That will certainly make wax look better despite few bicycles operating under those conditions unless your chainring digs into the ground at regular intervals.

After wasting time with a few exchanges with Friction over FinishLine Green, the insults were enough to make me stop bothering. The guy declares it’s NFG while admitting he’s never tested it while claiming to have contacted FinishLine who said that was not the case when I contacted them. Doesn’t come across as very honest or truthful IMHO.

Hard not to think the guy started out as a wax-cultist who designed his own test protocol to produce the results he wanted and then used ’em to sell overpriced bags o’ wax and liquid waxes to the converts.

I don’t care if people wax their chains, mustaches, bikini areas or whatever, what annoys me is the obnoxious implications that if you’re not in the cult, you’re a moron…but that’s the way cults work, right?

other than indoor oval track racing, it’s difficult to point to any discipline where dirt doesn’t get thrown onto chains as your rear tyre is whizzing by it at all times, carrying whatever is on the ground on the chain. we’re talking 6-7 grams of lubricant inside the chain, so even 4-500 milligrams of the stuff can be a significant amount there to contaminate it

Any oil or wet lube is just going to transport contaminants to the rollers of the chain, and attract more dirt. I sling enough mud at my bike to not need to sling mud elsewhere lol. Waxing for us MTBers in the muddy, loamy, rainy Pacific Northwest area has been absolute win. I don’t do immersive waxing even though I recognize it would provide the best protection to the chain, give me another watt or two to carry my immense ass up the trail, and make my chain last a few hundred more KM’s. Drip waxes get most of the way there, and that’s good enough. I’ve used the wet and dry chain lubes and all of them absolutely gunked up the chain. Now, I get home, wash off the bike, it dries off in front a fan. Waxing chains is good sense, and they’re only cultists if the data doesn’t back up what they say. ZFC has literally tested candle wax and shown it to be better than every other lube. I have done candle wax (yup – just a lit candle dropping globs of wax on the links) just for laughs on one of my bikes that gets the most KM’s and hilariously, the chain wear has been near zero. ZFC isn’t going to last long if his data is bullshit. And no lube company has sued – why? because his data could be proved in court? So: the testing protocol is sensible, I’m using products that last way longer than the stuff I used before, and if I want, I can use candle wax and tell the whole chain lube industry to sod off. And I like that the chain and drivetrain stay so clean while I do it. So yeah, the smart people are waxing.

“ZFC isn’t going to last long if his data is bullshit” Why? He makes it look like his biz is testing things for lube companies for a fee, but is it? My guess is his biz uses all that “research” and “testing” to promote the immersive waxing products he sells. His data being BS (or not) doesn’t really matter to the wax-cultists…they’re sold and enjoy watching videos telling them how smart they are to pay $50 for bags o’ wax pellets vs the clueless morons who drip some oil on their chain when needed. I’ve written plenty of times that I don’t CARE what the wax-cultists do, what I resent is the implication that people not in the cult are ignorant…but that’s how cults work, isn’t it?

Having read the above article I don’t think Hambini understands the point of open testing protocols?

If something meets a standard or has published results for a specific test, people need to be able to see what tests were carried out to achieve those results or refer to the standard to verify its requirements.

Adam’s testing protocol is open for review, so people can rightly ask questions if they feel they need to.

This doesn’t seem to be the case for Hambini’s previous tests, other than being referred to read a book to learn the founding principles. If the text contains the test or standard used, just refer to the section where it is presented? The way this was handled by Hambini wreaks of elitism.

There are some descriptive and technical responses on this page combined with some name calling from the opposing view.

My opinion is that the article makes less and less sense as it progresses.

Long time Hambini fan who discovered silca wax about a year ago. Came on here after seeing the ZF video after it was recommended to me on Yt.

I’m a wax convert for sure after thoroughly testing it as I thought it was BS. I’m done using chain cleaner and just using boiling water now. My current chain has already surpassed my last one by 1000 miles and park tool is not even close. Clean this chain and the last chain monthly so no real time difference. Just less mess and no greasy rags.

How safe is the chemical in the silca wax really vs what’s in liquid chain lubes is what I’m really curious about. I just know my mild ocd when it comes to maintenance on my bikes that I do plan on sticking with wax.

Why does the HSC Cer chart in the article show a consistently higher life of bearing for all load cases for hybrid ceramic bearings as compared to steel bearings?

Hello Hambini,

I think there area few problems with your take on waxing, ZFC and their testing.

Does hot waxing your chain confer real life advantages?

in my experience ( a couple of months, two road bikes), yes it does. As the chain manufacturers and you pointed out, the key is cleanliness, and this is where waxing has a benefit. The chain is dry, and in practice doesn’t collect grit . I am very fastidious about keeping my drivetrain clean (chain off and immersion cleaning weekly with wet lube), and keeping the drivetrain clean is just much easier with waxing. overall less maintenance

The wax doesn’t flake off, even if you shift gears. I use Silca wax, which has proven an absolute pain to get off anything without applying heat. A lesser man than myself might think you made an assumption

Chain manufacturers are not paragons of truth and reason; they sell stuff. Some claim the factory grease is infinitely superior to anything the costumer can apply. This is obviously bollocks; most any oil will do. I also had a KMC factory rep tell me to expect a lifespan of maybe 2-3000 km from my DLC 11 speed chain. Well, I got one anyway. I retired it after running it from 2015 to 2024!

Measurement accuracy and repeatability. In terms of watts saved I’m inclined to agree with you, in the sense that the setup needs some work. The equipment choices don’t seem to be up to the minute differences ZFC claim to measure.

I think the setup is the same for all products though, so wouldn’t it be valid as comparative data obtained on the same rig?

Chain elongation is not a accurate indication of chain friction. It is, however, the only metric used by the makers to determine when to retire chains in most applications. Make of that what you will

Do I feel a reduction in friction? Only in the sense that the chain doesn’t pick up, and retain, any shit. And it seems quieter; seems being the operative word here.

Waxing chains is a tried and trusted method for motocross and enduro (just straight parafin wax in my day) for sandy conditions. Friction isn’t really a factor once you got an engine in the equation, but reliability is king in racing.

As stated above, I don’t really care if someone is pro waxing or not. I am only stating what Sedis and Renold’s reps said. They did say a few further things that will come to light when the video comes out.

For me, it’s the ridiculous claims that come out from these lube companies that tips me.

Amen to that.

I think its actually a problem that almost anything greasy will work on a chain, and nothing very dramatic happens with a suboptimal product. So no SAE to set standards for our particular application.

I have personally, in a dire emergency, used lard (yes, molten pig) for the chains on a forklift. I worked ok, but went rancid and smelly a lot quicker than I expected. The level of unsubstantiated tech fiction is out of control in cycling; even the beauty-industrial complex is subjected to some scrutiny.

Is the average, common or garden, cyclist that gullible?

Hello Hambini,

I have a Titanium bike, and bottom brackets are prone to get eaten by corrosion. Generally the aluminum get eaten, so presumably galvanic corrosion. My current (Rotor UBB 4630) bottom bracket have been holding up for years; its ceramic, but surely that can’t be a factor in regards to corrosion? on my winter bike i use something cheap, steely and cheerful. Generally speaking they last a year at best. Any thoughts?

When it does eventually die I’ll get be getting a Hambini, though;-)

Just curious – is there a drain hole in your BB shell for condensation or water that gets in..to get out? If you wash the bike regularly, no matter where you live I find it hard to believe your BB’s are failing so quickly, ceramic or otherwise.

I generally wash my bikes weekly; a bit longer on dry roads at the height of summer perhaps. My bikes both have drain holes, and I remove the bolt to drain/inspect during washing.

Generally speaking they remain dry, even the winter bike is very rarely wet inside. It goes inside at either end of the ride to/from work which might account for the lack of condensation in the frame.

The winter bike gets deep pitting in the aluminium part (threaded ITA standard), to the extent that 2-5 mm of the inner part of the thread is missing. Turns into a powder accumulating at the bottom of the BB shell. To my mind classic dissimilar metals corrosion, and considering the modest torque I cant see strain corrosion being a factor. I replace when the BB starts feeling gritty, and at that point the races are affected as well by corrosion. Its not the end of the world, I just replace with something cheap and cheerful.

The strange thing is that my fancy(ish) Rotor BB on the sunny day bike just last and lasts, it’s essentially as new. This bike admittedly sees very little rain, but it is fitted in titanium BB shell and only really protected from contact by astronaut snot (titanium fitting grease) I’m not complaining, mind you, just very puzzled by the difference.

“My bikes both have drain holes, and I remove the bolt to drain/inspect during washing.”

So the opening (hole) is plugged with a bolt the rest of the time? If so, that’s not a drain hole, it’s a plugged drain. Campagnolo says drain HOLE, something I make sure all of my bikes have, even if I have to drill it myself.

You shot yourself in the foot with this one Hambini, I used to hold you in quite high regard and trusted your judgment and videos,

I suppose the proof is the difference I have seen over the years having switching to waxed chains, I suggest anybody who has doubts try it, but I will say there is more work and time involved with waxed chains

I’m not really an advocate of waxing or using wet lube. However, from practical experience (i.e. riding in northern Europe), rain is inevitable, and I’ve generally found the wet lube to be better. Wax tends to come off when it’s wet.

Check Friction Fiction’s friend’s latest zootube. The one where (horrors) he suggest adding…OIL for extreme conditions. But of course it’s only oil he sells…at almost $400 a liter vs the Mobil 1 SHC 75/90 gear oil I buy for less than $20 a liter. “Fools and their money” as they say!

Drip waxes are a great compromise. No mess from oil, and still solidifies around links and rollers, a far better situation compared with oils where grit will inevitably work its way into the chain. I mountain bike in Canada through all 4 seasons so the benefits of waxing are high. If you’re in SoCal I suppose oil would work just fine.

I would highly recommend reading the first paragraph. This isn’t about the merits or otherwise of chain waxing, its about the testing methodology that comes to the conclusion that it is the best. It might still be the best, but its irrelevant to the piece being presented.

Personally I wax, not because it makes me fast or gets more life out of the chain. I wax because I find it more convenient.

I wax 4 chains once per month whilst I service my bike, its part of my hobby. The time it actually takes is only a few minutes, however, the process can take about 20 mins for the 4. I change a chain once per week or 200km ish, for me thats all a waxed chain will last before it get noisy. “Who has time for this”? Well, anyone who wants to stop watching tv for an hour every month. Most spend several hours per day watching shit on tv.

In my opinion a waxed chain is cleaner and dislike using oils each ride, its just my preference for when a get a flat. I could not care less about the cost savings. Like most people here I ride a very expensive bike so im good for a $50 chain a few times per year to peruse my hobby and stay fit.

I would agree ZFC, Silca and everyone else who sells average over hyped products should be called out. That said, they are running a business and in the bike business most over promote and under deliver. Sure you could pay $20 too much for your pot of wax, but hey, its not so bad. You could have paid half a mil to buy that shitty 40 year old house of yours. I would say those who purchased the wax got off lightly. In other words, everyone is having their trousers pulled down by someone.

ZFC are also selling bent wire for hanging you chain up for $20, you don’t need anyone to tell you this is not good value. Same goes for your $10000 plus bike and your house that you have to work like a donkey for, for the next 30 years.

What this sees to exemplify to me above all is the paucity of accurate testing and data to back up marketing claims by lubricant manufacturers. In that informational black hole, it is quite easy for someone with limited knowledge and means, who is ostensibly just trying to give people information (most charitable explanation) to gain a following.